A yellowing letter, more than 50 years old, is framed on my study wall. It’s a reminder of the confounding gap between a country’s aspirations for its citizens and the political conditions needed to make that reality. It’s also a reminder of the paradoxes of hunger. Let me explain.

As a young teenager, I was just beginning to explore the political world and my place in it. I browsed my parents’ weekly news magazines, asked questions, and rode my bike to the local library where I read about other countries and their leaders. My teenage girlfriends had autograph collections of local personalities, so I wondered: What if I wrote to international leaders? Was there any chance they would write back? I began sending handwritten letters to heads of state around the world, asking for their autographs. To my shock, within weeks responses started to arrive—from offices of presidents, prime ministers, and the occasional member of royalty.

The President’s Hopes

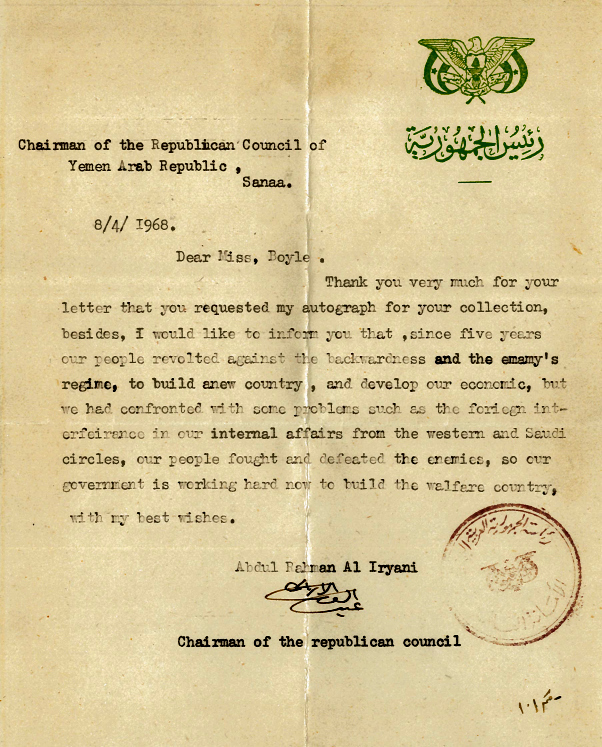

In 1968, one arrived from Yemen’s President and Chairman of the Republican Council Abdul Rahman Al Iryani. Below is a scanned copy of the letter, postmarked from Sana'a, Yemen (pictured above). In laboured English put to paper on a ribbon-style typewriter, he spoke of the struggles of trying to build a country despite foreign interference from “western and Saudi circles,” and his hope for economic development and a “welfare country.”

That he took a few minutes, in tumultuous times,[1] to write to an unknown Canadian teenager, says a lot. He was proud of his country, mindful of how it was perceived abroad, and clearly he cared about young people. Brief though the letter was, it was also a moving statement of this leader’s aspirations for the future of his people.

I’ve never been to Yemen. A small nation on the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, it apparently has a fascinating culture and history. But today we mostly hear about Yemen in the context of its struggles. It’s the poorest country in the Arab world, and imports about 90% of its food.[2] For the past five years Yemen has been wracked by bitter conflict, with each side aided by other countries protecting their geopolitical interests. The hostilities have ravaged the domestic economy, agriculture, and food distribution: for example, just a few months ago, aid workers from the World Food Program finally got access to a warehouse in Yemen that held enough grain to feed 3-4 million people for a month and that had been inaccessible for months due to the war.[3] Most of its 30 million citizens are dangerously food-insecure, famine conditions are spreading, and citizens from babies to adults are dying from starvation.[4] The World Bank has declared Yemen the planet’s biggest humanitarian crisis.[5]

Famines: Failures of Governance, Not Nature

By no means is pervasive hunger in Yemen a result of a natural disaster. From a December 2018 press report on Yemen:

Geert Cappelaere, Middle East director for UNICEF, the U.N.’s emergency fund for children, said authorities on “all sides” of the conflict are impeding aid groups — and increasing the risk that the country will descend into widespread famine.

“This has nothing to do with nature,” Cappelaere told the AP. “There is no drought here in Yemen. All of this is man-made. All of this has to do with poor political leadership which doesn’t put the people’s interest at the core of their actions.”[6]

The internal and external causes of hunger in Yemen echo themes from my reading about another historical era when devastating human conflict and an epic failure of leadership led to preventable deaths by hunger. In 1943, a famine claimed 2-3 million lives in the Indian province of Bengal. It was due less to crop failures than to conditions created by British and Indian war priorities and the privileging of elites over the rural poor.

Many renowned writers on famines -- such as Amartya Sen, Cormac Ó Gráda, and Thomas Keneally -- have explained that most famines do not solely result from natural disasters over which people have no control. Some stem from human conflict that causes chaos and wrecks societies, and some also from economic systems that – at least indirectly -- funnel food to the rich rather than the poor. Famines result more from failures of governance and of equitable food distribution, than from acts of nature or God.

Nearly 11% of the world’s population still isn’t getting enough to eat.[7] Fresh, nutritious, sustainably produced food is economically out of reach of many people even in mid- to high-income countries. Although Ó Gráda’s research offers the hopeful insight that widespread famines are less common than in past centuries, Yemen shows that hunger is far from over. Conflict and violence are still among the main drivers of hunger and food insecurity around the world, and climate change is bound to create political and economic conditions that exacerbate this.[8]

Food Security A Shared Challenge

Yemen’s Prime Minister Abdul Rahman Al Iryani passed away in 1998, and while the ink on his letter has faded with time, the impression his pro-youth gesture made upon me has not. As my forthcoming book on British food policies in the Second World War comes together, I’m seeing how important it is to understand food-security challenges in countries as different as mine and his. We are all Earth’s citizens, equally deserving of peace and sustenance, and our fortunes are increasingly linked.

[1] The Independent April 1998 Obituary: Qadi Abd al- Rahman al-Iryani

[2] Relief Web: Missiles and Food: Yemen’s man-made food security crisis

[3] NY Times Feb 2019. UN Seeks $4 billion to save billions from famine in Yemen

[4] NY Times Feb 2019. UN Seeks $4 billion to save billions from famine in Yemen

[5] World Bank Yemen country overview

[6] Associated Press AP Investigation: Food Aid Stolen as Yemen Starves

[7] UN FAO: 2018 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World

[8] UN FAO: 2018 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World

Learn more about famine causes:

- Sen, Amartya. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. 1981. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. Famine: A Short History. 2009. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton U Press.

- Keneally, Thomas. Three Famines: Starvation and Politics. 2011. NY: Public Affairs.

About Yemen:

- Yemen Economy 2019.

- Kane-Hartnett, 2018. Yemen’s Crisis: A preventable famine or a political end?

- UN News 2019. 10 million Yemenis One step away from famine’, UN food relief agency calls for Unhindered access’ to frontline regions.

- NY Times Feb 2019. UN Seeks $4 billion to save billions from famine in Yemen.