Today I'll focus on a question I occasionally encounter from people who hear me talk about meat.

A hidden agenda?

Imagine this scenario: A public health expert is speaking with a school class of teenagers, outlining reasons not to start a cigarette habit. If you start smoking in your teens, the expert says, you’ll most likely still be smoking when you’re 40. And the scientific evidence shows that you’ll then be much more likely than non-smokers to get cancer, or have a heart attack, or be vulnerable to a host of additional ailments.

Then imagine that one of the young people asks the expert if she herself is a smoker. “Why, no,” she replies. So the teenager retorts: “Then why should I believe you? You don’t smoke, so on this topic you’re biased!” The teenager is saying that the expert is not objective. She has a hidden agenda.

If you’re like me, you’d be stymied by this logic. Critical thinkers would say the health expert would be more likely to raise eyebrows if she knew the science on cigarettes -- but was a smoker nonetheless. If she believes the evidence, you'd expect her to act on it!

The truth is out

Once in a while when I'm giving a talk or writing an article suggesting that average consumers eat too much meat for sustainability and should cut back, a listener/reader will suggest that because I personally choose not to eat meat, I must not be objective on the topic, and should declare my "conflict of interest."

I am happy to disclose that I don’t eat meat, and have not done so for more than 25 years. Not actually a vegetarian by most definitions, I do eat small amounts of fish and dairy. But to suggest that my meaty decision makes me biased is just as questionable as the assumption from the hypothetical teenager.

Which comes first -- the dietary choice or the analysis?

For one thing, it's not at all clear why meat-eaters (especially those who have strong emotional, cultural, or financial ties to meat-centred diets) would have some greater claim to objectivity than those of us who choose plant-based diets. What makes carnivores objective on the subject of meat?

But more importantly, to label me as biased is to confuse the direction of causality. When I say the average consumer needs to eat less meat, I’m saying it not because of my own dietary choices, but because that’s scientifically sound. I made my choices after evaluating the evidence and finding it persuasive.

Latest research concurs

Here are just a few of the latest studies that provide strong evidence for more moderate global meat consumption:

- The world must cut back significantly on meat consumption, said the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) just a few months ago: Read about it in this 2019 issue of Nature. In Aug. 2019, Reuters also reported on the United Nations/IPCC conclusion that global meat consumption must fall to curb global warming, reduce growing strains on land and water and improve food security, health and biodiversity.

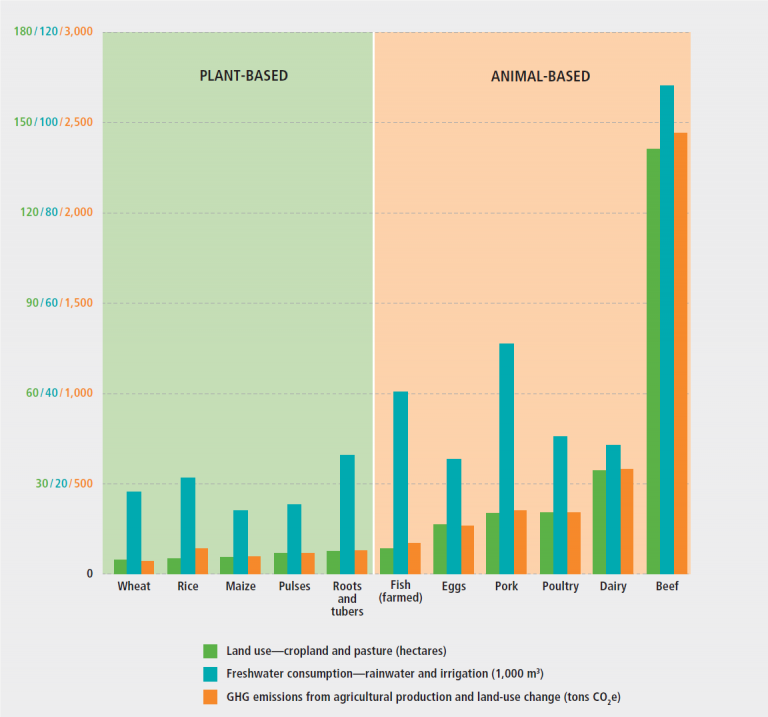

- To make food systems sustainable, three main dietary shifts are: (a) that the billions of us who overeat cut back on calories; (b) that consumers in wealthy nations reduce excessive intake of animal-based foods; (c) that we specifically reduce consumption of beef, which is resource-intensive to produce: Report Shifting Diets for a Sustainable Food Future by J. Ranganathan et al. (2016) for the World Resources Institute. More on two powerful steps for eating sustainably: Eat fewer animal-based foods, and waste less: Researchers R. Waite and B. Lipinski (2017) for the World Resources Institute.

- To transform our food systems in ways that are crucial for sustainability, we’ll need diets “rich in plant-based foods and with fewer animal source foods,” and increased intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes. EAT Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health (2019).

Researchers have been offering strong evidence on this for years. But the data are now incontrovertible that global warming gets a hefty contribution from too many livestock and too much meat. I too can say this, because I am an experienced and credible researcher on this subject. That’s the real test – not what a person eats, but the rigour of their research.

Let’s go out with a quote from an IPCC official who was involved in that latest IPCC study: “We don’t want to tell people what to eat,” says Hans-Otto Pörtner, an ecologist who co-chairs the IPCC’s working group on impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. “But it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect.”

It would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect. -- Hans-Otto Pörtner of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

The graph below [from J. Raganthan et al. 2016. “Shifting Diets for a Sustainable Food Future.” Working Paper, Installment 11 of Creating a Sustainable Food Future. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute; Figure ES-2] summarizes the impacts (land-use, fresh water, and greenhouse gases) of plant- vs. animal-based diets.